|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| May

19— Paul

Ladis can’t see his three daughters or his wife of 15 years, Beth. The former

machinist from Roselle, Ill., has been legally blind for a decade. He was born with a

hereditary disease called retinitis pigmentosa, a gradual decaying of the retina which

affects 100,000 Americans and can lead to total blindness. Last

year Ladis's brother told him of a company called Optobionics whose doctors were

implanting the first artificial retinas. Ladis, 45, applied to be a test subject and,

a few months later, walked into the Rush-Presbyterian-St. Luke’s Medical Center in

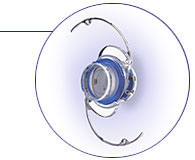

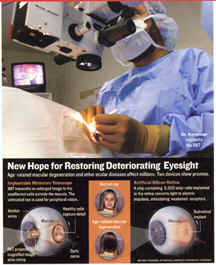

Chicago. Today, a silicon chip two millimeters across sits in his eye, converting light into electrical signals that travel through the optic nerve to his brain. The technology is still in its infancy and offers no hope of a total cure. But Ladis says he now notices shapes, lights and motion instead of an inky gray darkness, and can function better around the house. “If I want to reach out and hug my kids, I can see them walking by me now,” he says happily. Ten years ago, the idea of placing a tiny electronic device into the human eye seemed more suited to sci-fi than reality. Compared with the ear, where cochlear implants have been effectively converting sound into electrical impulses since the mid-’80s, the eye is a more sensitive and complex piece of human anatomy. But today, a dozen teams of scientists around the world are pursuing the goal of artificial eyesight for those who spend their days in darkness. They’re proving that such technology is safe, and that it can improve the quality of life for the vision-impaired. Like Paul Ladis’s bionic implant, the new devices do not cure ocular disease, and none are approved by the FDA for general use. Yet early promising results have spurred cautious optimism among ophthalmologists that the age of combating blindness has finally begun. “The concept is no longer laughable,” says Gerald Chader, the chief scientist for the advocacy group Foundation Fighting Blindness. “There are patients living with implants that seem to work.” The most prevalent disease researchers are targeting is macular degeneration. The affliction, which affects an estimated 11 million (mostly elderly) Americans, leaves a foggy black splotch at the center of the field of vision. Patients often must use huge closed-circuit TVs to magnify newspapers or books, or big, unwieldy head-mounted telescopes. The Saratoga, Calif. based VisionCare wants to lighten their load. The IMT (Implantable Miniature Telescope) evolved out of Israeli research into optics and is roughly the size of a pea. Inserted into one eye like the intraocular lens in cataract surgery, it projects a magnified image over a wide field of the retina. After an hour long procedure, patients must undergo extensive training to learn to use the implanted telescope for central vision and the other untreated eye for mobility and peripheral vision. The device, now in FDA trials, has been implanted in more than 70 patients, and VisionCare scientists are very optimistic about early results. “For an 80-year-old to sit and watch TV or read headlines in a newspaper or pay their bills, it’s a godsend,” says Robert M. Kershner, MD a Tucson ophthalmologist involved in the trials. (Dr. Kershner Performs the IMT Surgery)

Robert M. Kershner, MD, FACS, Eye Laser Consulting, e-mail: Info@EyeLaserCenter.com, website: |

For More Information on the Implantable Miniature Telescope call Vision Care's toll-free infoline at 1-888-528-0006 of visit their website at